|

The Power of Internal Dialog

Internal dialog (aka interior monologue, interiority, or free indirect speech) is a narrative technique used to relate a character’s internal thoughts. Internal dialog differs from stream-of-consciousness in that it consists of formal, coherent sentences rather than the more free-form, unstructured ramble of stream-of-consciousness; the playwright’s soliloquy (Is this a dagger which I see before me, the handle toward my hand? Come, let me clutch thee) is its theatrical equivalent. Although generally considered a post-modernist technique, both Jane Austen and Tolstoy used internal dialog to good effect in their novels. Internal dialog is one of the most powerful tools at the fiction author’s disposal. Properly deployed, it can perform a number of functions, often at the same time. The technique can deepen character, reveal inner states and conflicts, carry setting description, convey backstory, give insights (often slathered with judgement) into other characters, and far more. Best of all—and this is a little-understood truth—although internal dialog is a narrative rather than dramatic tool, when properly used it feels authentically, 100 percent like showing rather than telling. Consider the following narrative ("telling") excerpt, and note the filtering words (set in boldface): She slammed her door and fell into the chair, thinking how badly she'd let him down. She told herself she should have been there for him. She knew she could never face him again. Now here's the same excerpt represented as unfiltered (filtering words dilute the effect) internal dialog, using italics to flag it as interiority: She slammed her door and fell into the chair. God, I let him down so badly. I should have been there for him. I’ll never be able to face him again. Stronger and more effective than the first narrative example, right? Furthermore, the Italics are not vital, and in fact the effect may be stronger still without them. Here's the same sentence without italics: She slammed her door and fell into the chair. God, I let him down so badly. I should have been there for him. I’ll never be able to face him again. See what I mean? Not only no filtering, but direct with no italics. And yet, you understood that the first-person bits represent the character’s direct thought in their own head, right? Just be clear in your own mind what is what is interiority and what is narrative, and all will be well. With this in mind, here’s a little scenario to practice the technique: Your protagonist is out on a birthday dinner date after a punishing breakup, and their new love interest has chosen the restaurant and kept it a surprise. As they arrive at the restaurant, your protagonist is shocked to see that it’s their ex’s favorite place, and—it being Saturday night—there’s a good chance of running into him/her. Write 100-200 words of internal dialog to encapsulate and convey what passes through your protagonist’s mind as they pull up to the restaurant: try to get it down fast in a continuous pass before doing any polishing. Bonus points for making your protagonist the opposite gender to yourself. I try to leave out the parts that readers tend to skip

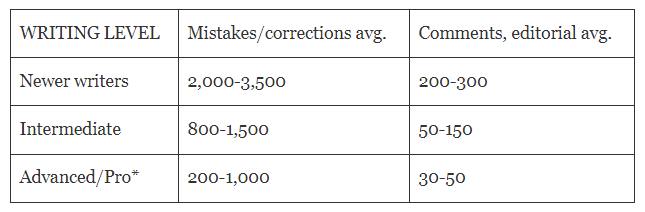

-- Elmore Leonard If a scene or passage doesn't advance the plot or is boring to write, you quite likely don't need it. Self-Editing: The Inconvenient TruthSome while ago, I found myself reassuring an author on Twitter. The author had shown someone their final novel draft, which they’d gone through countless times, and the reader found a number of mistakes in just the first ten pages. This isn’t in the least unusual. And although there’s currently a rash of books and blog posts on how to self-edit, the reality is that you’re not — unless you’re already a seasoned pro, and even then — going to catch the majority of issues with your own work. It’s impossible. I’m not talking about typos here, or even commonly confused words (discreet for discrete, effect for affect, etc.), missing quotation marks, and the like, all of which will slip past spellcheck and most authors’ revision passes. No, the dangers lie in far more significant errors such as plot holes, continuity glitches, confusing passages of insufficiently-tagged dialogue, impossible actions, viewpoint slips, mangled syntax, and so much more. (More here on what good copyeditors look for and how they go about it.) The two main reasons self-editing doesn’t really work are that the author is so familiar with their own manuscript they can’t read it slowly enough, and (worse) they understand their own creation so well that they’re not going to see the holes and missing links that will prevent the reader from fully understanding or following it. Looking back over dozens of manuscripts I’ve copyedited in the last several years, I find the following rough metrics emerging (based on 80,000-100,000-word novels): Sobering numbers? They should be. Other editors I've spoken to report similar numbers.

Now, bear in mind that the mistakes/corrections listed in my table above will include a large number (up to 50%?) of quite minor issues, such as punctuation, paragraphing, indents, etc. Still, punctuation errors can change the meaning of a sentence; and although most readers are somewhat forgiving if the story is engaging, if the text has repeated errors, they’ll likely ding the author in a review, or put the book aside for good. With between one and three thousand new books published every day in the US alone (yes, you read that right) and millions of books for sale on Amazon alone, the competition for the reader’s time and money is beyond ferocious. And although good editing/copyediting doesn’t come cheap,** the author who publishes a book without having a professional go over it is taking a big risk. As for the editorial comments column in the table above, those usually constitute actionable items or issues – plot holes, say, or something not believable, or worse — serious enough to require flagging for the author. Things that need fixing, or at least consideration. Some authors may also be a little wary of copyeditors, because they see the process as inherently adversarial (“red pencil syndrome”), or because they’re concerned about having their style altered. These aren’t unreasonable concerns: as an author myself, one of my guiding principles is to respect the author’s style and intention and make every effort to hew as close to their original text as possible when making corrections or suggesting changes. Perfect examples of this are sentence fragments and even comma splices: while most copyeditors will unhesitatingly treat each instance as a transgression, I try to determine if they’re intentional stylistic choices; if there’s no significant grammatical issue, the author gets the benefit of the doubt. And many authors have thanked me for respecting their style choices. Secondly, I try (if it’s not an obvious case) to give the author an insight into the reasoning behind my strikeouts and, at the risk of seeming overly didactic, to supply any applicable rule behind errors I see repeated, in the hope this may help the author in future. It’s true that good beta readers, if you’re fortunate to have some, will catch quite a few things. But even the best readers aren’t going to spend twenty minutes recasting an awkward paragraph (it’s very rare to find a manuscript that doesn’t have many), check your facts, scrutinize capitalization use, address incorrect punctuation, monitor for consistency, and so on. It’s unlikely they know their style manuals inside out, or have the broad array of general knowledge a good copyeditor should. Given they’re doing this as a favour to the author, they’re unlikely to give a ms. the close and careful scrutiny and the time a copyeditor will. Finally, copyediting is not critique. If your betas are writers, there’s also a good chance some of them may have their own ideas of how your story should go, and that’s not always a good thing. Copyediting is a necessary and valuable step in preparing a manuscript for publication, and an investment in both the current work and the author’s career, whether they’re indie publishing or going the traditional route. Are you interested in having your work copyedited? Drop me a line! Notes *The very cleanest manuscript I ever saw was from a longtime professional who’d written dozens of novels and short stories. In the whole 80k words, I only made thirty corrections and eight comments. One of these, however, was a doozy: at the pinnacle of the climax, the hero gets the chance to draw his pistol, saving the day. Unfortunately, he already had both hands full, a catch for which my client was very grateful indeed. **Copyediting an average length novel takes anywhere from thirty to sixty hours and up, depending on how much work is required. It’s intense, high-focus, and highly skilled work, and a good copyeditor is worth every penny they charge. The Inelegant Question of Language Drift

|

|

Scroll down for more articles

|

Language changes. In fact, languages change so much as to become largely unrecognizable over a period of six or seven centuries. Middle English from around 1350 is at its best difficult for us; Old English of 1,000 years ago is indecipherable. This process is generally termed semantic drift or semantic progression.

Yet even knowing this, we’re very resistant to any changes we see occuring in our language today. It’s a knee-jerk, almost territorial reaction: we blather about the purity of the English language ignoring the reality that, with its origins in the Germanic tongues and heavy borrowings from Latin, Greek, French, and Dutch, the English language is anything but pure. In the words of James D. Nichol, “The problem with defending the purity of the English language is that English is about as pure as a cribhouse whore. We don’t just borrow words; on occasion, English has pursued other languages down alleyways to beat them unconscious and rifle their pockets for new vocabulary.” At our last meeting, there was some discussion of the word elegant. Someone—I can’t recall who—correctly pointed out that the term had drifted in meaning and was still used in some fields (e.g., science) to indicate simplicity or economy, as in the phrase an elegant solution. This meaning is still inherent in the term, although relegated to a secondary meaning today. My OED defines the word thus: Elegant Adj. 1. Graceful and stylish 2. Pleasingly ingenious and simple Today the word is generally understood to mean classy; and if I look up classy, I see that word is defined as an informal adjective meaning “stylish and sophisticated.” Elegant, then has become the formal term for this meaning. How did we get here? The root of the word elegant comes from two Latin words. The first, eligere, means, “to pick out” or “to choose,” the root which gives us the words, elect, election, etc. The second, elegans, which came to English via Old French, originally suggested taste and discernment—which involves choice. The website etymonline.com sums this up well (note my underlines): elegant (adj.) late 15c., “tastefully ornate,” from Old French élégant (15c.) and directly from Latin elegantem (nominative elegans) “choice, fine, tasteful,” collateral form of present participle of eligere “select with care, choose” (see election). Meaning “characterized by refined grace” is from 1520s. Latin elegans originally was a term of reproach, “dainty, fastidious;” the notion of “tastefully refined” emerged in classical Latin. Related: Elegantly. Elegant implies that anything of an artificial character to which it is applied is the result of training and cultivation through the study of models or ideals of grace; graceful implies less of consciousness, and suggests often a natural gift. A rustic, uneducated girl may be naturally graceful, but not elegant. [Century Dictionary] Thus, what was once a term of reproach--elegans as “dainty, fastidious”—has now drifted to the extent that what was once a slur has become a compliment. Elegance, however, got off lightly. Consider the fate of the word gay, which in my childhood was still used to indicate jollity; today, I’d be wary of telling someone they appeared gay. Or decimate (Latin decimatus), a word which is today used to mean near or total destruction. When I hear it used this way—which is all the time—my immediate instinct is to decimate the speaker, since the word actually means the death of one in ten; with its origins in the Roman military practice of punishing a cohort of troops by executing one in ten men, the word’s very root (decem) means ten. The drift of the word nice is a very interesting case in point. Nice has a variety of meanings, including polite, agreeable, well-bred, virtuous, and even exact. However, nice was not always so: originating from the Latin nescius (“ignorant, not knowing”), the word historically meant foolish, wanton, and dissolute. Many other words in English have done a similar one-eighty, among which silly, which originally meant happy, blissful, lucky or blessed in accordance with its root, the old English word seely. And on top of this, new words are created and officially added to the dictionary/ies all the time, with many having their origins in the computer fields, as well as social media. In my editing work I frequently correct usages which haven’t yet been offically sanctioned, though I know I’m fighting a rearguard action: the times they are a-changing, and the language with it. Before I leave the topic, I want to pass on a link which I think many of you will find interesting: https://books.google.com/ngrams/ Clicking on this will lead you to Google’s ngram viewer, which allows you to see the frequency of a word’s occurrence over time in tens of millions of scanned texts. Just clear the search field and type in your own word. https://books.google.com/ngrams/ Have fun with it. And next time someone tells you something was decimated, please smack them upside the head. They deserve it. |

|

Questioning Critique

|

|

It’s been said that a writer fluctuates between believing they’re the best writer in the world and the worst writer in the world—and in some cases, that they hold both views at the same time.

The point is well-made. When the creative faculty is fully engaged and the characters on the page writhe and pulse with life, the writer is in heaven; but when the inbuilt editor that any good writer possesses kicks in, or the work runs aground on any of a myriad possible shoals, the writer is convinced his work is crap. Writers work in isolation. They’re very close to their work. And a piece of fiction is a dynamic, interdependent, sometimes fantastically complex web of forces and relationships. It’s therefore vital, as the work approaches its final completion, for the writer to get outside feedback. Over the last dozen years I’ve participated in or mentored several critique groups, as well as founding one (“Written in Blood”) several of whose members are now widely published and have even won major awards. I firmly believe in the now standard writer’s group critique process. And yet I’ve begun to see its limitations. Bear with me as I take approach my point obliquely. I’ve written elsewhere about my dislike of the way the publishing industry, steered as it is by suits and the pressing imperatives of the market, is increasingly adopting the Hollywood approach, where everyone gets input on the final result. I personally know of several authors whose book was turned down by a publisher because the marketing department had issues with it (sometimes just because it didn’t fit a clear category) despite the fact that the editorial team were unanimous in approving and wanting to acquire it. My point is that when we try to second-guess, we can always, always find issues; and in addressing those issues, we end up making so many changes that we suck all the life and uniqueness out of a work. Today, a book is first critiqued, often multiple times, before going to the author’s agent, who often initiates a whole new round of revisions; and then the same occurs at the publishing house. This in my view is why so many genre books today seem generic, formulaic, and about as exciting as the kind of art that hangs in bank lobbies and Comfort Inn rooms. I’m beginning to think that the word “critique” itself is problematic (the etymology goes back to the Greek word, krités, a judge) and tends to slant the process of towards fault-finding; “evaluation” may ultimately be closer to what a writer needs, but I’m probably splitting hairs. Let me be clear: I do believe writers should seek critique and feedback,. and am not for one instant devaluing the formal writers’ critique group. But as we grow as writers, we need to be really sure that the type and direction of critique we’re receiving is keeping pace with our skills, and that our beta readers “get” our work and our intent. Writers need to be very aware that it’s easy to critique anything to death. Tangents and irrelevancies creep in as the well-meaning critiquer casts around to address anything which may raise a question. In this fishing process, things may be caught which actually materially and subtly contribute to the flavour and uniqueness of the story; but in their doubt, the writer, once alerted, may remove the item, and in the process diminishes the final work, bringing it closer to the ordinary. As an example of this, imagine a Gothic. claustrophobic tale set in a remote castle. In the process of critique, one or more readers may feel that they want to know more about the world outside. What’s going on there? Why doesn’t anyone in the castle go down to the village for supplies? Where do they get their water? And so on. These questions may be fair and even relevant, but there’s every danger that an insecure writer, in attempting to address them to please some theoretical contingent of readers, begins to put in sentences or scenes or infodumps which degrade the atmosphere of isolation and claustrophobia and consequently lessen the power of the work. Even more of a minefield is the advice frequently given in critique about adverbs, flashbacks, show don’t tell, etc.; while all the standard writing advice is founded on very solid principles, it takes true maturity to understand its limits; and likewise to know how and when to break the rules. The point of critique isn’t to make the story or book attain some theoretical ideal of perfection (ideals which are usually based on writerly dogma and oversimplified writing “rules” than anything else); the point is to end up with a publishable piece of fiction which readers will enjoy and which communicates the creator’s vision in as unalloyed a form as possible. The mature writer needs to have the self-confidence and feel sufficiently secure to say, “no: enough”. Perhaps this is why most pro authors, or even those those who are multiply published, seem to move on from formal critique groups and instead pass their manuscripts on to a very small, handpicked circle of other mature authors for beta reading, people who they know will “get” exactly what they’re striving for, and what the reader wants, rather than taking more of a scattergun approach to finding fault in the manuscript. The line may be a fine one, but it is, in my experience, very real. To my mind, the best beta readers and editors will understand the distinction between on the one hand fully respecting the author’s intent, direction, vision, and style, and on the other, obsessing over some cookie-cutter notion of what the market wants and what constitutes good writing. The focus needs to be on two things only: what the writer intends, and what matters to readers. Nothing else. Because it’s about the reader. And that’s all it ever was about. |